Dawn of the Planet of the Apes hit the screens for most of Europe on 17 July and is the latest film to ignite talk of motion capture technology, whereby cameras track the movements of actors from reflective markers positioned on their bodies. The technique allows film studios to create digital characters, such as the apes in Dawn of the Planet of the Apes, from the movements of human actors. It used to be the case that the technology would be confined to a room in front of a green screen, but around 85 per cent of the footage of this film was shot outside the studio, a testament to the advances made in motion capture.

Marker-based systems have been the staple for motion capture, but markerless technology is becoming progressively more reliable and is now complementing or competing with those systems based on markers. The absence of the bauble covered suits makes the systems quicker to set up, provides a more realistic acting environment for the performer, and certain systems – such as the ones offered by New York-based Organic Motion – allow for real-time animation of video footage.

University education and military training industries are making use of this technology, according to Jonathan Beaton, director of marketing for the company, and the markerless systems offer a cheaper alternative for Organic Motion’s clients in the entertainment business, which include the likes of motion-capture giants, Ubisoft Montreal and Warner Bros Games.

Unlike the more established marker systems, which use light collected from either active or passive indicators that are placed at strategic points on the actor, Organic Motion uses full frame video footage from what

Beaton described as relatively run-of-the-mill cameras with powerful software to track the entire subject. He said: ‘Initially we tell the software that we are looking for a biped and ask the actor to stand in a T shape. This allows the system to calculate how long each of the limbs are and how tall the actor is.’ The algorithm then uses this information, combined with its knowledge that it is tracking a biped, to understand how the subject is likely to move.

Recording a performer’s motion in this way requires controlled illumination and thus has to take place within a plain walled room with consistent lighting. The company’s main studio uses 18 cameras that are all linked to the central computer via FireWire in order to handle the vast amounts of data fed in from the camera array. The amount of data from the cameras gives rise to what Beaton describes as the biggest problem with the company’s system.

Because there are limits to the amount of data that the system can process, this imposes limits on the number of cameras and hence on the physical size of the room – the workable volume – in which the motion is being captured. Workable volume is the issue that they are currently trying to overcome. Recent developments have seen more than 30 cameras linked up successfully and, while this is not yet commercially available, would allow for larger volume studios. Beaton said: ‘With a big markered system, you can run and jump over a very large area, but we are constrained to 24 x 20 feet. That’s our biggest limitation.’

In the future, as the lines between the two methodologies begin to blur, Beaton said that everyone is hoping that the technology will move towards the markerless system. ‘No one likes putting those suits on. As our systems get larger and larger, we may see an increase in the use of this type of motion capture.’

However, he concluded: ‘If there is one thing that is interesting in the markerless versus markered conversation, all of our clients still use marker-based systems. I don’t see the technology as competing at the moment; it is more of a complementary component. That’s how we look at it here. No one has bought markerless and then got rid of their marker tracking technology. Markerless is easier to use and it’s better for the animators, but you still need to get big area shots, so people still need the markered systems. The idea is that they have to do less stuff with the bigger systems at marker-based studios, which can be expensive to hire. Having a markerless system means you can get most of the stuff done and limit the amount of time in the big studios.’

Beaton added that game studios might make use of both marker and markerless systems in tandem, but universities, which are a big market for motion capture, would typically only purchase just one system. Organic Motion recently secured a deal with a university for its system due to the advantages of it being markerless.

Another difficulty for both marker and markerless systems is movement being obscured from the line of sight of the camera, or occlusion. It is one of the main reasons that so many cameras need to be used in a motion capture system. By introducing more cameras, the chance of capturing movement is greater. However, Philip Elderfield, Vicon’s product manager for entertainment, still thinks occlusion is the biggest challenge for the vision-based systems.

‘The director and the cast need accurate real time feedback when shooting. Occlusion can cause problems for this. You can, in post production, account for and accommodate a certain degree of blocking, but this is very hard to do in real time; if you can’t see it you can’t track it,’ continued Elderfield. ‘We now have advanced algorithms and techniques in our software that can use all the available information to work out where the marker is likely to be when it can’t be seen by any camera. We have done tests where you take off 80 per cent of the markers or lay a blanket over a person lying on the ground and the system still works.’

One thing that interests Elderfield for the future is the fusion of different methods in motion capture. ‘Each has its pros and cons but fusing the data could allow us to take the advantages and compensate for the limitations of each approach. I suspect this is the way the industry will move in the future.’

Elderfield said: ‘There are broadly three main types of motion capture: video based, which is often markerless; optical marker tracking; or inertial sensor based. Inertial systems use an array of inertial devices, similar to the devices used in a Wii controller or an iPhone to detect orientation and movement. These are placed at strategic points on the body and feed information back to a central system to build a skeletal picture of what the actor was doing. While these can provide data even when in the line of sight of a camera, they tend to suffer from precision drift over time and can be affected by metallic, magnetic or other environmental influences. The precision of such systems is still a long way off that of optical systems.’

He said: ‘The general idea is that the vision-based systems could help to fix the drift from which the inertial tracking suffers, while the inertial system could fill in the blanks if occlusion caused problems for the optical system.’

Recently Matt Parker, senior motion capture technician at Centroid, has noticed that head-mounted cameras for facial tracking have become increasingly popular. ‘In the future we are going to be marrying up different technologies such as the Occulus rift [virtual reality system], and creating a virtual studio. This would mean that actors would be able to immerse themselves within the virtual world. Currently, the bar for talent has to be quite high because an actor may have to portray a lost girl stumbling around in snow in the Himalayas. In reality, they would be wearing a full suit with markers on in a studio, in the middle of July, just outside of London. So anything that could aid the performer in achieving this would be desirable.’

On your marks

Studios that provide motion capture are the ones most likely to benefit from this fusion. Centroid, which operates out of the prestigious Shepperton studios in the UK, most commonly uses a passive marker tracking system, explained Parker. ‘This means the actor is required to wear a suit with small reflective dots on it. These tend to be rubber spheres that are covered in 3M tape, similar to that found on high-vis jackets. To illuminate the markers, the lens is surrounded by an infrared strobe that pulses at around 60Hz and this light is reflected by the markers and picked up by the sensors.’

Parker said: ‘All of the systems work in a similar fashion to the Satnav in a car; if the Satnav was the marker, the cameras would be the satellites. So in the same way that you need multiple satellites to triangulate the Satnav, you need multiple cameras in a system to generate accurate positional data of the marker.’

He also warned that while having more markers on the actor tends to be better in terms of data accumulation, it may impede the performance.

For complex scenes, such as multiple actors performing a fight scene, the system needs to be able to differentiate between actors. In close proximity to one another it could be difficult to distinguish the leg from actor A from the arm of actor B. To combat this Parker explained: ‘When we have an actor in, we will position the primary markers which produce the raw amount of information that we need to capture the skeleton of the performer. We will also add secondary markers that are positioned to provide a signature for each actor, as well as providing more information as to how the body part moves.’

The system also reads the distance between the markers and identifies the actor from this. Actors may all be different heights and sizes which means the markers would be different distances apart and the system can use this to recognise which arm belongs to which actor.

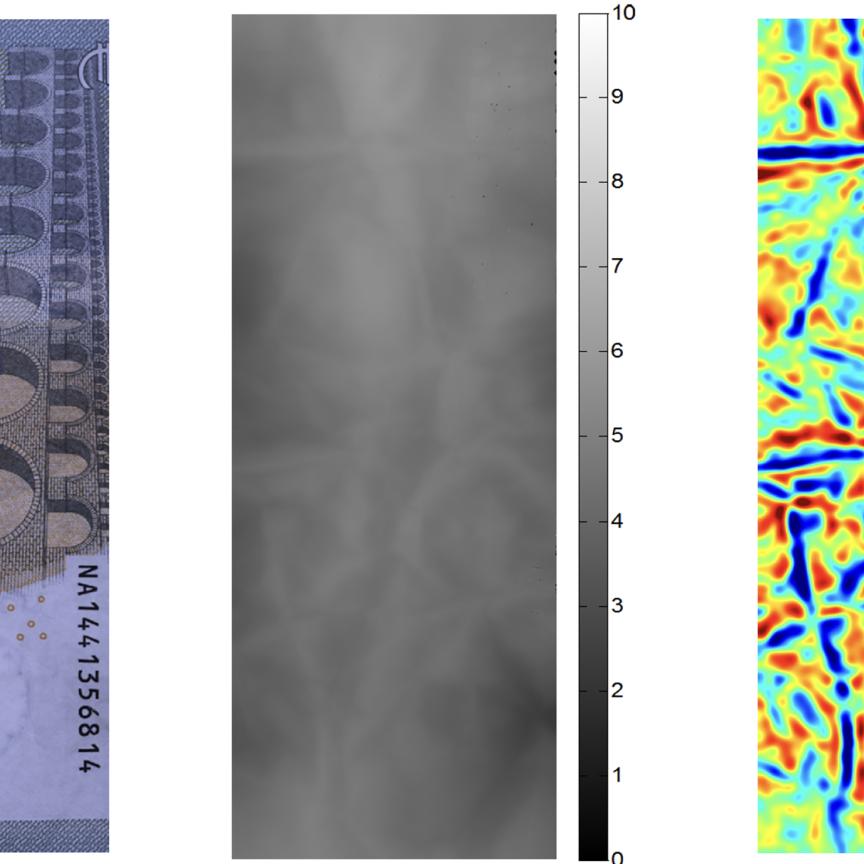

The company’s three most commonly used camera models, the Eagle 1, Eagle 4, and Raptor 4, are supplied by Motion Analysis, based in California, USA. Eagle 1 and 4 are one and four megapixel models respectively, but can only be used indoors. Parker said: ‘The Eagle models work on the principle that if there is enough infrared light, it produces a black pixel; if there is not enough light present it leaves it as a white pixel. This can make it very difficult to distinguish between the light from a marker, a cloud, or from sunlight. Sunlight also produces enough infrared to make nearly everything throw infrared light into the camera. There is just too much information for the camera to process.’

The Raptor cameras, however, can work outdoors, away from a green screen. The Raptors use greyscale, which allows the camera to not be so overcome by the amount of light hitting the sensor and more successfully differentiate between different intensities of light.

Vicon’s Elderfield stated: ‘More and more people are taking optical systems out on set and filming on a full “hero” set. You would be shooting a movie in the same space that you are shooting the motion capture. Some actors are being motion captured but others are not.’

In the past, these systems needed controlled environments to obtain useable footage. ‘Varying lighting conditions and other occurrences on a set can prove difficult, so we have to make our systems work in such dynamic and uncontrolled environments.’ concluded Elderfield.