On the 50th anniversary of the Moon landing on 20 July 1969, Zeiss has described how, in less than nine months, it built the camera lens used to capture the iconic images during the Apollo 11 mission.

The customised Zeiss Biogon 5.6/60 ‘Moon lens’ had to work with an easy-to-use camera, while also being able to map the lunar surface around the landing site.

‘The time for development was extremely brief,’ said Dr Vladan Blahnik, who works in research and development at Zeiss.

The optical data for the preceding model, the Zeiss Biogon 4.5/38, still had to be calculated manually, an extremely time-consuming process. However, a mainframe computer helped to determine the mathematical parameters for the Zeiss Biogon 5.6/60 Moon lens in two weeks.

Dr Erhard Glatzel (1925-2002), a mathematician from the optical design department at Zeiss, received the Apollo Achievement Award for this and the development of other special camera lenses for space photography.

Blahnik explained that NASA decided on a camera fitted with a Reseau plate, which created a grid of cross-marks on the images. These made it possible to calculate the distances between individual objects on the Moon.

‘The special symmetric design of the camera lens provided an excellent correction for distortions and all other image errors,’ Blahnik said.

Overall, 1,407 photographs were taken on the Apollo 11 mission, using nine film magazines. All images are available online. A total of more than 30,000 photos were captured with Hasselblad cameras and Zeiss lenses during all the Apollo missions.

The astronauts received special training on how to use the camera. Their helmets made it impossible to look through the viewfinder, so they had to learn how to photograph more or less blind, Blahnik said. They wrote down on their gloves the shots they wanted to take, so that they wouldn’t forget anything, he added.

Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin spent around two and a half hours walking on the Moon, during which time they had to keep returning to the lunar module to wipe the lens clean, according to Blahnik.

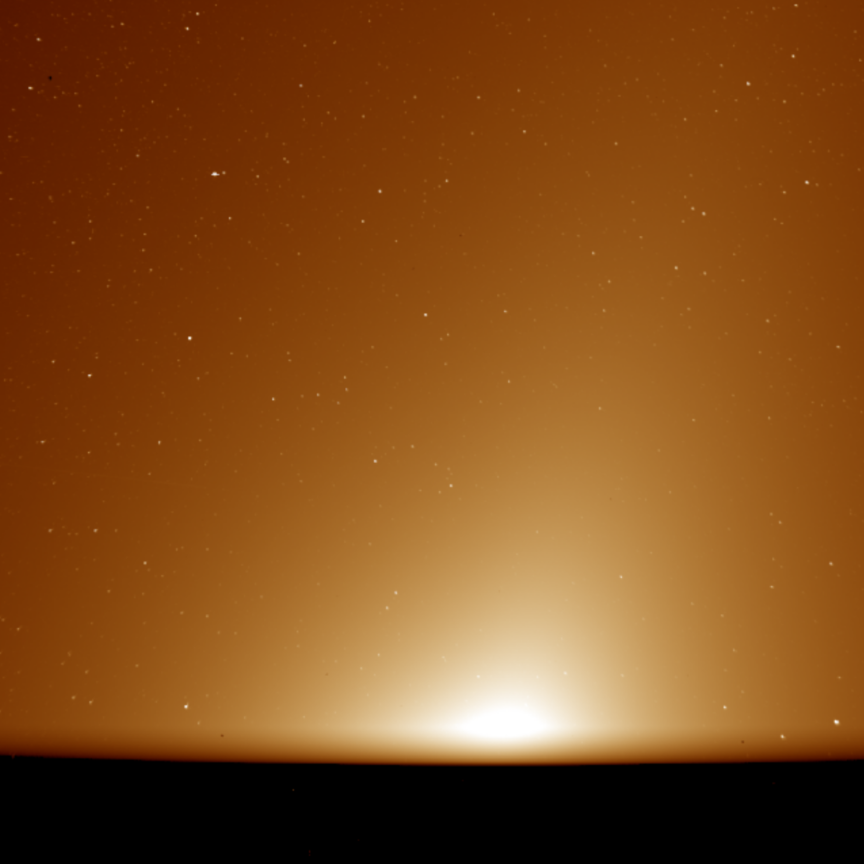

The camera settings were mostly fixed in advance and then slightly adapted according to the position relative to the sun.

‘The definition and brilliance of the images taken on the Moon’s surface speak for themselves,’ commented Blahnik. ‘In a picture such as the “Man on the Moon”, which has been greatly enlarged subsequently, small image sections such as the tiny letters on the astronaut’s suit still boast high definition and contrast. The detailed panoramic photographs enabled us to create an exact map of the landing site.’

Along with the lens for the Apollo missions, Zeiss also designed a number of other special camera lenses for space photography in the 1960s, among them lenses that could transmit UV waves or extremely fast lenses such as the Zeiss Planar 0.7/50.

The engineers at Zeiss continue to benefit from this research today. Some examples are the development of fast lenses for professional movie cameras, lenses for aerial photography used in surveying the Earth’s surface, and lithographic lenses employed in the production of microchips.

The cameras with the Zeiss lenses are still up there on the Moon, because on the return journey the astronauts wanted to save weight in order to take back as many samples of Moon rock as possible. Only the exposed film made it back to Earth.

--

The registered Zeiss brand ‘Biogon’ denotes a special wide-angle lens. ‘Bio’ exemplifies ‘vivid’, because this type of lens is characterised by wide apertures and short exposure times, making it possible to capture vivid, moving images. The ending ‘gon’, derived from the Greek word gonia, meaning angle, is used for several wide-angle lenses designed by Zeiss. Current Zeiss photo and cine lenses still bear the names Distagon or Biogon today.